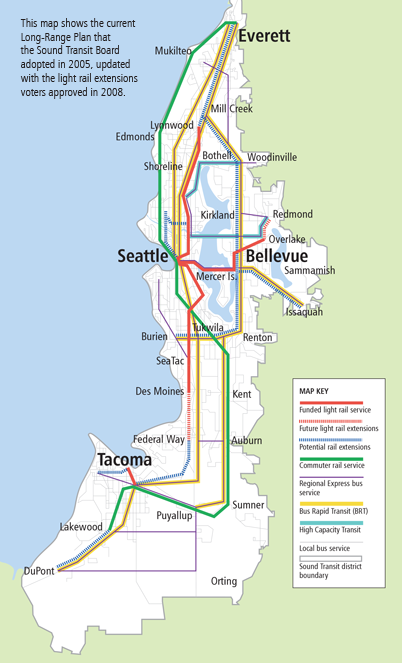

Sound Transit, the Seattle area’s regional transit provider, and the primary planner and builder of rail transit in the region, is updating its Long Range Plan.

I suggest modifying the Long Range Plan Map in three places:

1. Add a West Seattle potential light rail extension, from downtown Seattle to Burien. Sound Transit has already scheduled a study of high capacity transit in this corridor. This link will connect a Hub Urban Village (West Seattle Junction) with downtown Seattle and the Burien regional center, from where the Long Range Plan already shows a potential rail extension. The transportation geography of West Seattle is particularly favorable for transit ridership. All travel north or east of the “peninsula” must cross bridges in either the Spokane Street or 1st Av South corridors. Transit already has a high mode share of downtown commuters due to favorable bus treatment on the West Seattle Bridge and SR 99. However, the SR 99 tunnel will result in longer travel times and more congestion in the transit path. Providing a completely grade-separated rail route between West Seattle and downtown will provide attractive, speedy and reliable transit service that will be well utilized. This project should be considered for the ST3 funding package.

2. Add a potential light rail extension connecting the rail extension in Ballard to the high capacity transit route from Northgate to Bothell. This connection rationalizes the potential rail extensions into a single line from downtown Seattle to Bothell via Ballard and Lake City. This addition will connect the Hub Urban Villages of Ballard and Lake City to the Urban Center of Northgate. This project should be considered for funding in the ST4 or future funding packages.

3. Change the line paralleling I-5 between Seattle and Tacoma from Bus Rapid Transit to High Capacity Transit. High capacity transit is defined in the Long Range Plan as either BRT, light rail or commuter rail, mode to be determined. This change in designation allows for future consideration of commuter rail in this corridor. By the mid-21st century, the Puget Sound region should consider a new mainline rail corridor directly connecting Tacoma, Sea-Tac airport and downtown Seattle. The corridor would be used for a second Sounder commuter rail line (all-day, two-way) and for regional high-speed rail (Cascades). The line could utilize the I-5 right-of-way from Tacoma to south of Sea-Tac airport, the right-of-way for the proposed SR 509 extension from I-5 into Sea-Tac airport, and a bored tunnel under the airport and continuing underground near SR 99 to meet the BNSF mainline near Boeing Access Road. This project should be part of a true long-range plan, to be implemented in cooperation with a high-speed rail authority.